Postcard Promises: Tourism at the End of the World

The hope of pristine and picturesque wilderness, adventure, fresh air, and memories forged with friends and family is the siren song of the outdoor tourism industry. Utah, in particular, is a destination for many seeking this type of experience. It is home to five national parks that comprise over 1,300 square miles of geological and historical wonder: Arches, Bryce Canyon, Canyonlands, Capitol Reef, and Zion National Park. High chroma photographs that accentuate the fiery red-rock formations against ethereal blue skies are the bait to entice would-be adventurers to traverse the desert landscape and stand in silent and meditative awe of Mother Nature.

When visiting a national park, there are a number of factors that unexpectedly frame the experience. Travelers have to negotiate vacation time, reserve campsites, buy equipment, plan their road-trip playlists, pack their vehicles, drive for hours on end, haggle over bathroom stops, find palatable roadside dining, circle parking lots, work with shuttle schedules, set up camp at often congested sites, deal with pit toilets, and hike in unfavorable weather. When the perfect picture is to be captured for posterity, a vantage that excludes all the other posing tourists, upraised camera phones, and distracting detritus can be nearly unattainable. It is akin to pilgrims traveling to Paris to view the Mona Lisa in the Louvre, only to find that the desired intimate and quiet communion with the artwork is impossible as they are jostled by the swarming and camera-happy crowd in front off the diminutive artwork sitting distantly behind barriers and bullet-proof glass.

Images of national parks found on postcards, social media, and park websites consumed prior to a vacation shape visitors’ expectations as they look forward. Then the photos and videos taken by tourists cement and mold their memories as they look back. The roads, trails, and signage direct movement and attention to the primary attractions and photo ops. The pristine wilderness exists only as a myth to the sightseer since their experience is highly guided, mediated, and manicured. Often, direct rapport with the earth is not even desired. Campers bring with them all the amenities they can in their cars, trucks, SUVs, and RVs—creating a portable, bougie, suburban home with a national park as their front lawn in search of an idyllic #vanlife.

Our national parks were initially envisioned as part preserve and part playground, and these two interests are continually colliding. Access to protected land results in the scarification of the earth with roads and trails, restrooms, and visitor centers. It is this type of interference and mediated experience that irked noted author and one-time resident of Arches, Edward Abbey, who wrote, “Arches National Monument has become a travesty called Arches National Park—a static diorama seen through glass.”1

Artists Katie Hargrave and Meredith Lynn were fascinated by Utah’s national parks, not solely for the landscape, but for the thing that Abbey despised: the cloud of surrounding tourist culture—from the postcard promises of leisure and adventure to the nitty gritty of camping. Outfitted as proper vacationers with a rented van and a teardrop camper, the artists set out to visit all five national parks in Utah in the early spring of 2020, counter to Abbey’s insistence that it was “better to idle through one park in two weeks than try to race through a dozen in the same amount of time.”2

Starting their trip outside of Epicenter in Green River, UT

As John Steinbeck noted in his American travelogue, plans, schedules, and intentions are for naught as trips cannot be completely controlled. Hargrave and Lynn’s trip was cut short as fears surrounding COVID-19 began spreading across the nation in March and organizations began to shut down, including national parks. Fortunately, the abbreviated itinerary allowed them to fly home the day before a 5.7-magnitude earthquake manifested just southwest of the Salt Lake City Airport, forcing it to shut down on the day of their original departure. This same earthquake damaged property in downtown Salt Lake City including the historic Rio Grande Depot that houses a gallery space where the artists were scheduled to exhibit the fruits of their collaborative trek through Utah’s national parks. Their exhibition was postponed indefinitely while repairs took place and COVID restrictions were enacted. Their original plans were dashed to “wreckage on the personality of the trip.”3

The artists were able to pivot and still exhibit their work at The New Gallery at Austin Peay State University in Tennessee, November to December, 2020. References to the work in this essay are based on their exhibition at The New Gallery titled Over Look / Under Foot.

The project started in Arches National Park. In advance of their trip, they scoured the internet for Creative-Commons-licensed images previous sightseers had taken of popular vistas of Arches National Park, including other people in their shots. The artists pasted these photographs of red rocks and blue sky together and had them printed onto fabric that would be fashioned into their campsite tent. When erected at the campground in Arches, the tent became a strange form of camouflage that both hid the structure within the similar landscape and caught the attention of other campers because of its unique appearance. In the gallery, video of people photographing themselves and each other in the park were rear-projected onto the tent’s doorway.

The Arches tent in situ (left) and installed at The New Gallery at Austin Peay State University (right)

In 1971, when Arches was designated a national park, the number of annual visitors was 202,100. In 2019 (pre-pandemic), 1,659,702 individuals came through the park.4 On peak days, the park can see over 3,000 vehicles pass through its gates.5 This dramatic increase of car and foot traffic means more roads, parking, pollution, trash, and the creation of the single developed campground in the park featuring restrooms with flush toilets. It was at this campground that the artists pitched their tent highlighting the increasing human presence in the park.

Moving on to the next nearest park, Canyonlands, Hargrave and Lynn covered the windows of their camper leaving only one small hole as an aperture, effectively turning the interior into a camera obscura to capture all seven scenic overlooks as they drove through Canyonlands National Park. The resulting photographs were exhibited as they were captured, with the landscape upside down, having been inverted by the aperture. Because the photographs were taken from the vantage of the camper, without the aid of zoom lenses, the images don’t quite resemble the typical tourist pics that seek desperately to mimic professional promotional images. Instead, the camera obscura photos contain the picturesque views as well as roadside gravel, concrete parking bumpers, and road signage. They are more honest images that do not crop out the manmade facets that frame the sightseer experience.

Camera Obscura: Capitol Reef

Photography and video are such integral parts of tourism. Pics or it didn’t happen. Whereas static photography is ideal for capturing single vantage points, video is for journeys. Using the same camera obscura setup, the duo shot a video of the sixteen-mile round trip drive along the paved roadway through Waterpocket Fold in Capitol Reef National Park as the passing scenery cascaded across the camper’s interior cabinetry. The external was brought internal, as if the camper were an eye on wheels, continually watching.

At Bryce Canyon National Park, the artists turned their lens on the visitor center. They shot video around the center and gathered found footage of old national park promotional videos and vacation films from the 1950s and ’60s. Ultimately these videos and films manifested in a work at The New Gallery. Their found footage and video of the visitor center were placed inside graphic arrows found in and pulled from driving manual diagrams to assist drivers with maneuvering a vehicle with an attached camper trailer. This video was rear-projected inside another custom tent similar to their Arches tent. The nylon shell remained dark except for the slivers of the footage shimmering through the arrow’s outlines scattered across the tent’s taut fabric, like constellations guiding travelers in the night.

Bryce Canyon Tent

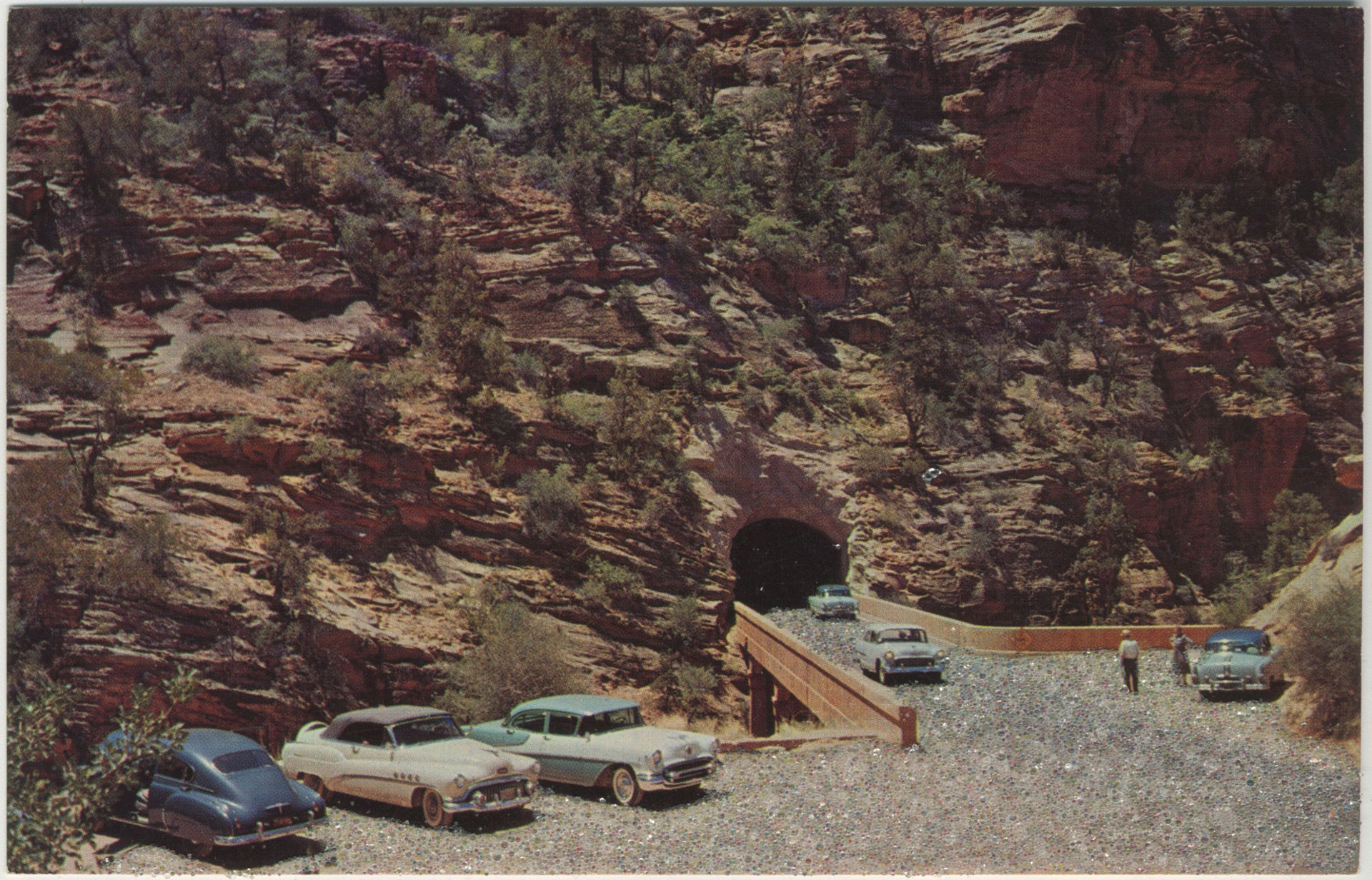

The last stop was at Zion National Park, the busiest of all the Utah parks, receiving 4,488,268 travelers in 2019.6 This concentration of traffic has led to unique solutions at Zion, including a new seasonal shuttle service. The road in and out of the park is often highly congested and the visitor center has a line of people awaiting information, brochures, and maps. However, as the artists arrived, they noted that the visitor center was closed. This was a symptom of COVID-19 as it began shutting down the nation in mid-March. Hargrave and Lynn were able to hike around the park, but not execute their original plan. Prior to the trip, they amassed vintage postcards of Zion, hoping to compare the old imagery with new ones in the visitor center gift shop. Instead, the artists sprinkled the roads depicted in their postcards with the tiny glass beads employed in reflective paint used to stripe roadways—drawing attention to this alteration of the landscape that literally paved the way for millions of visitors.

Altered vintage postcard of Zion National Park

Arriving in Zion—named in reference to a holy utopia—as the world began to crumble under a plague and earthquake, was an appropriately apocalyptic way for Hargrave and Lynn to end their trek. This land which was formed by seismic upheaval, now draws throngs to spend their leisure time hiking, camping, biking, and most importantly, photographing. On top of the strata of indigenous, colonial, and Mormon histories, is a new crust of millions of digital, geotagged images and videos. This latest geohistorical layer was the mine from which the artists drew the raw materials for their project. And it is back to this layer that their project returns, as images, videos, and texts such as this.

- Edward Abbey, Beyond the Wall: Essays from the Outside (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1984), xv–xvi. ↩

- Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire : A Season in the Wilderness (New York: RosettaBooks, 2011), 54. ↩

- John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley: In Search of America (New York: Penguin Books, 1962), 4. ↩

- “Arches NP,” National Parks Service, accessed March 16, 2021, https://irma.nps.gov/STATS/SSRSReports/Park%20Specific%20Reports/Annual%20Park%20Recreation%20Visitation%20(1904%20-%20Last%20Calendar%20Year)?Park=ARCH. ↩

- “Traffic and Travel Tips,” National Parks Service, accessed March 16, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/arch/planyourvisit/traffic.htm. ↩

- “Zion NP,” National Parks Service, accessed March 17, 2021, https://irma.nps.gov/STATS/SSRSReports/Park%20Specific%20Reports/Annual%20Park%20Recreation%20Visitation%20(1904%20-%20Last%20Calendar%20Year)?Park=ZION. ↩