Remember You Will Die

Humans have long grappled with a fear of the unknown—tackling the issue using narrative structures to prototype possible futures for themselves and civilization. Death, alien cultures, and illness have long been staples of art, literature, and movies. By mixing the real with the unreal, hypotheses are played out and tested on the page and screen to determine how to deal with these often terrifying scenarios.

Silk Flowers in a Vase With a Peony and Apple Blossom at the Top, 2018

Archival inkjet print

45 × 30 in.

In her work Impossible Bouquets: After Jan van Huysum (2018) Nancy Rivera subverts the tradition of still life, a phenomenon woven so deeply into the fabric of art history as to completely mystify a version without it. Her floral arrangements echo the historically performative nature of the still life as a tool to demonstrate the wealth of the patron and the virtuosity of the painter, while stripping it of these self-serving motivations. Rivera’s photos of artificial flowers and fruit, reference the painterly compositions of Jan van Huysum in 18th century Amsterdam. Van Huysum’s vanitas were closely related to memento mori, works meant to remind the viewer of the looming specter of death. He replicated and visually arrested the rapidly decaying flora in front of him as both a way to document the wealth of the patron who could afford the extravagant floral arrangements, and also as a reminder of the fleeting nature of life.

This echo chamber of iterative creations—Rivera’s reference to Van Huysum, who in turn references memento mori, which in turn references a struggle with death—parallels the idea of the children’s game “broken telephone” wherein each additional communication of the original idea further distorts the message and corrupts its meaning. The rich colors and plastic foliage of her photographs mask the foreboding and somber source material. In this way, her work functions as a saturated rumor of the original work, as well as its own self-sufficient series. In this process, Rivera places herself in the position of authority over the still life and its associated historical narrative in a contemporary setting.

The work of Jacob Haupt similarly focuses on reiterations and cultural investigations into the hereafter. His photographic series and accompanying art objects Did I Scare You? materialize and make tangible cinematic monsters. Following a long tradition of the animate depictions of death, disease, conquest, and human experience in the form of grotesque creatures, Haupt wrestles with death and fear using mythologies as a means to access and depict the unknown. His work disarms these monsters by using the awkward and goofy iconography that defines ’80s and ’90s B movies, children’s cartoons, horror films, and DIY halloween costumes. Haupt uses repetition of the mysterious, domestic materials, and bright colors to make the scary and mysterious, juvenescent and approachable.

Demon Chair, 2020

Inkjet photo print

20 × 16 in.

Right: Jacob Haupt

Window Creep, 2017

Inkjet photo print

20 × 16 in.

Creatures such as swamp monsters, zombies, possessed children, and others have been used in film, television, and books to personify mysterious evils, such as death, disease, and fear of the alien. Many of these mysteries have since become better understood and even tamed on a global scale, however fear and ignorance cannot be fully eradicated. Haupt renders these historical monsters harmless while acknowledging the residual anxiety and horror.

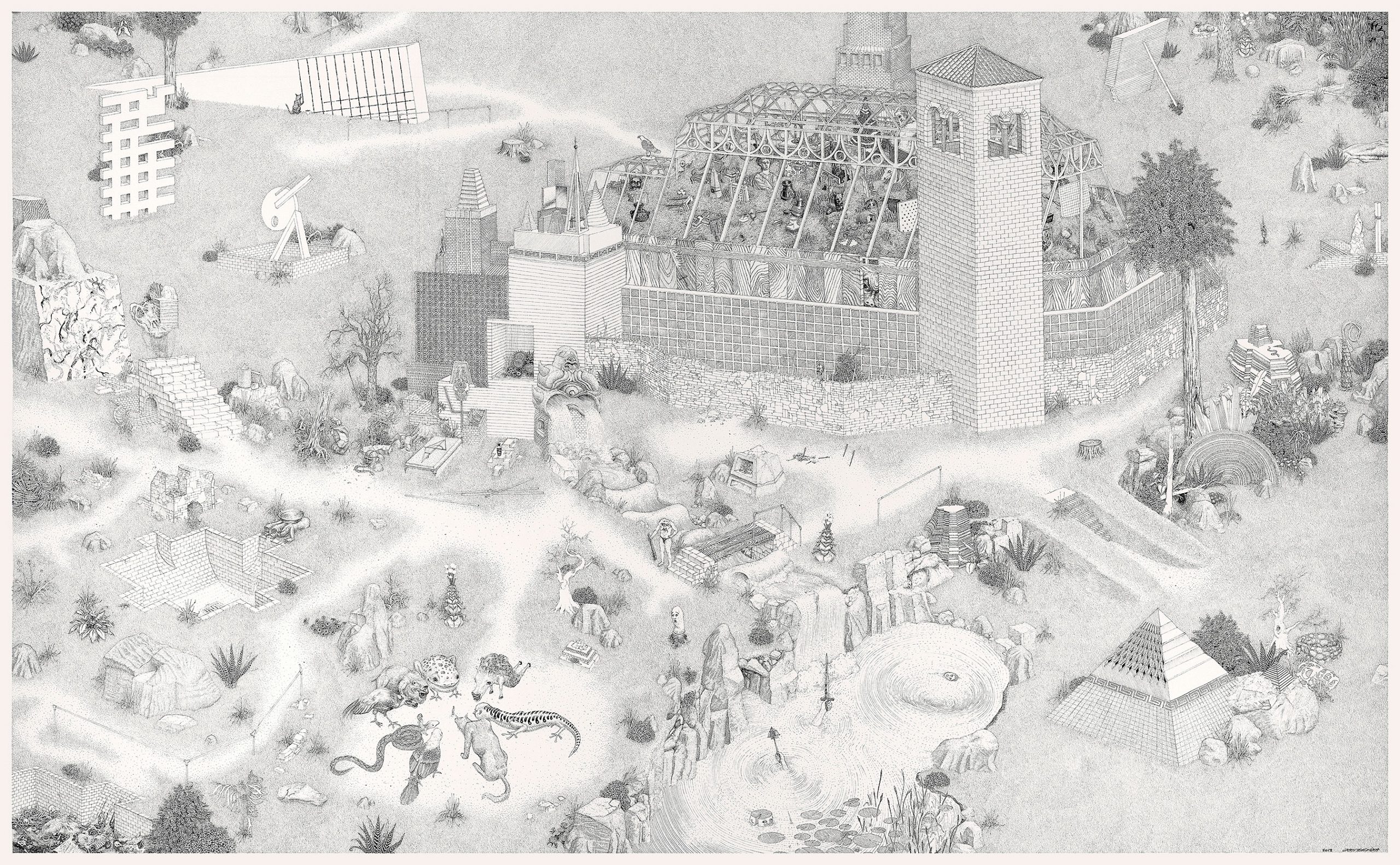

Haupt and Rivera’s work in collaboration functions as an intricate map of historical and pop cultural references which bleed into one another, further obscuring the source of the narrative with each step. The global nature of contemporary media promotes an ever-evolving web of cross referencing ideas, images, and motifs, further distancing itself from the doctrinal canons of art—each a reflection or ghost of what came before. Despite attempts to freeze time, cure disease, and defeat monsters, the inevitability of death shadows us all.

– Essay by Malachi Wilson, Christopher Lynn, and Janessa Lewis

Purchase Jacob Haupt’s Did I Scare You? book